Abstract

After a whole year of working within the narrow confines of the FTC rulebook with our students and feeling exhausted from a full season of competition, I was thrilled when we decided to wrap up the year with an ant weight battlebots competition among students, and mentors! This would be my first robot created as a robotics instructor, and thus high stakes. Students were excited by the prospect of beating me, and some scared by the possibility of facing off against whatever I created, so I had a lot to live up to.

Design

Inspired by being an intense Discovery and Science channels viewer growing up, I went all the way back to the beginning for inspiration and set out to create a miniature version of Jamie Hyneman’s Blendo from Battlebots predecessor “Robot Wars.” Not only was this my favorite combat robot for a long time, it was powerful enough to write new rules for the program and get banned from competition, which I took as a sign of the platform’s potential. This would be a full body spinner with a very small ground clearance to catch and transmit as much energy to flippers and other spinners of all kinds. Our one rule was a strict prohibition on metal spinning components, so this carapace would have to be a 3D printed part.

Fabrication

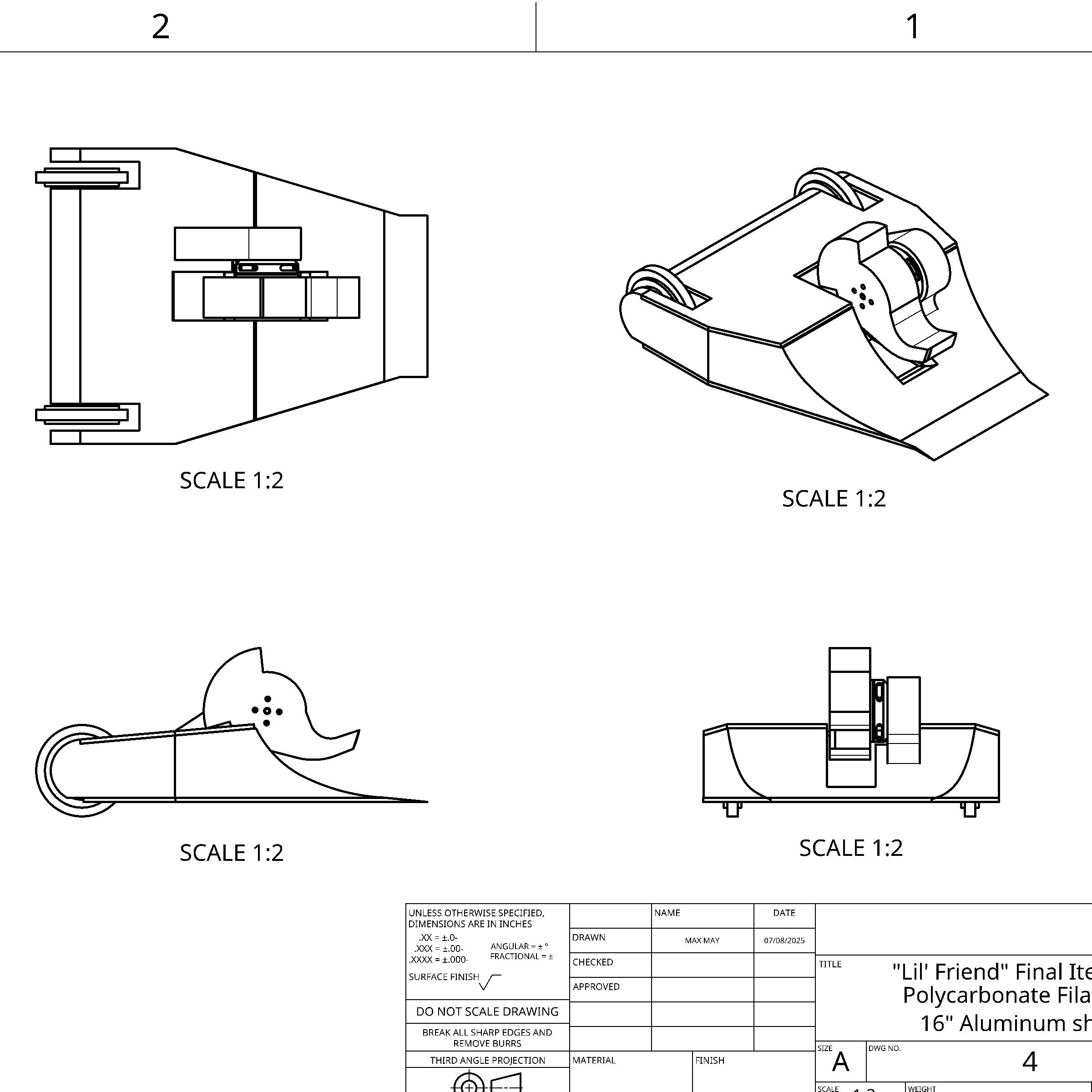

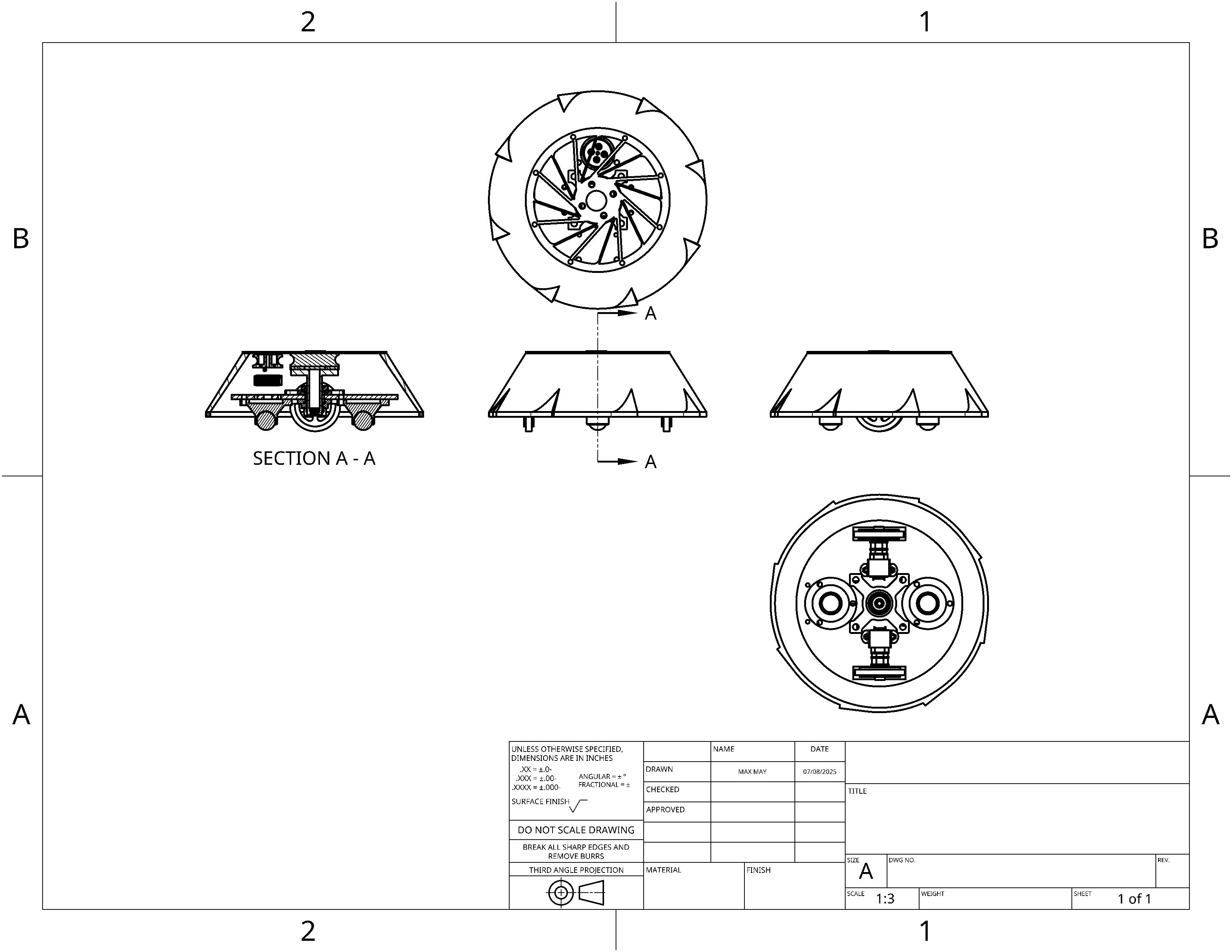

I started work on the smallest, lowest profile inner chassis I could manage with the stock ant-weight parts. The goal would be to make the drivetrain and control system as light as possible so all available weight could be placed in the shell for maximum inertia. The frame was a small disc, lightened between fastening points, that would hold a few goBILDA FTC parts, a servo hub and two 10mm ID bearings that would handle radial loads from impacts. The main shaft of the spinner would be driven off a belt reduction system from a hobby brushless motor turning very high RPM, This design also featured a fun idea, print in place roller bearings that would enable me to use a fully mobile differential drive mechanism that could change direction with minimal deflection, because I wanted my ground clearance front and back to remain as small as possible, this part was the only design that wasn’t iterated across versions of the spinner, the drivetrain frame was iterated once to contain a battery box and to reduce clearances against the spinner.

This was version one of the robot, which had a fun quirk of lifting off and spinning on its rim until it tore itself apart. I had no idea how to diagnose this lift problem, other than assuming that the main flaw was the relatively open top plate of the spinner, which I had initially designed as a separate aluminum piece. Version two would have a higher draft angle for even lower ground clearance, and a far less windowed top plate. Now I began to struggle with finding the right balance between ground clearance, spinner side-wall angle, and internal clearance. It was hard to keep a rake angle shallow enough that I could drive under other robots, while staying within the imposed 6” cube, and not rubbing inside the body on the delicate electronics, or battery… So version two was heavier, steeper, and didn’t generate lift, but now that these issues were sorted, I began to face this concepts fatal final two problems.

By having the contact point of the robot’s weapon above the ground plane at all, I was putting a tilting force on the robot that it just couldn’t recover from, all hits would knock the robot back on its rim, at which point anything and everything could happen to it, usually leaving it incapacitated. Second, at this scale, the spinner was putting too much torque on the motor, even with the round belt pulley system I had established, and was burning out ESCs and motors. After ruining my second setup, I decided to move on from this platform to something completely different.

Thus I started a bot based on the equally infamous Hypershock. This would be a rear drive wedge robot with a vertical single tooth spinner for launching opponents if not breaking them. Version one was very successful at causing damage, however this first layout still had a vertical envelope problem, as I put the differential drive in the middle of the bot, thus most protected from wheel damage, however this brought the potential for the bot to high-center, and given the way I was mounting my weapon motor, this meant that if the bot was ever flipped, it would have no way of moving.

The final iteration of the bot, called “Lil’ Friend” ditched some of the stock hardware for integrated motor mounts at the back of the robot, placing the wheels around a radius of robot body so it had full range of motion, this design used aluminum plates on the top and bottom around a 3d printed chassis. The bottom aluminum plate was thin, and sharpened to an even finer point for the greatest scooping potential, so I could drive under an opponent and feed them into my spinning weapon. This weapon was designed to have a nearly perfect center of mass despite the single tooth, and this single tooth would perfectly align with the sloped surface of the front wedge for the most potential contact. To give the greatest range of motion possible, the weapon was pocketed out through the bottom of the chassis, so the largest radius of spinner could be chosen. Finally, the weapon and control system were totally isolated from each other, so there was no potential for a broken weapon to damage the drive system, and the robot could operate in theory as a pushing wedge if the spinner was damaged. This robot was extremely successful in testing, so here is where I flew too close to the sun…

Conclusions

I was printing all these components at home with random filaments, and had the idea to branch out and purchase something way more robust than the PLA or PETG I had used thus far. Our battle chamber was made of Polycarbonate sheets, and we generally treat polycarb second to aluminum in FTC fabrication, so I found some polycarbonate filament and made the whole robot out of it with very little testing. In our matches I found that while PC filament is relatively strong, it shatters unpredictably. So while I did quite well up to a point, in the final match, my weapon literally split in half and lodged itself in the bottom of my robot, making it almost impossible to move. So I’m sure there are some design faults, but the main issue was the material properties of the final iteration, which I hope to test with either nylon or ASA for a more robust end product in the next competition that we do.